建造者模式/生成器模式

建造者模式/生成器模式

# TL;DR

Decouples the creation of a complex object and its representation.

对复杂对象的创建及其表示进行分离、解耦

# 意图

生成器模式是一种创建型设计模式, 使你能够分步骤创建复杂对象。 该模式允许你使用相同的创建代码生成不同类型和形式的对象。

# 问题

假设有这样一个复杂对象, 在对其进行构造时需要对诸多成员变量和嵌套对象进行繁复的初始化工作。 这些初始化代码通常深藏于一个包含众多参数且让人基本看不懂的构造函数中; 甚至还有更糟糕的情况, 那就是这些代码散落在客户端代码的多个位置。

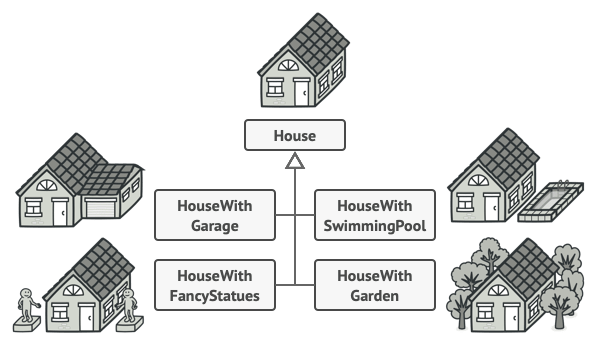

如果为每种可能的对象都创建一个子类, 这可能会导致程序变得过于复杂。

例如, 我们来思考如何创建一个 房屋House 对象。 建造一栋简单的房屋, 首先你需要建造四面墙和地板, 安装房门和一套窗户, 然后再建造一个屋顶。 但是如果你想要一栋更宽敞更明亮的房屋, 还要有院子和其他设施 (例如暖气、 排水和供电设备), 那又该怎么办呢?

最简单的方法是扩展 房屋基类, 然后创建一系列涵盖所有参数组合的子类。 但最终你将面对相当数量的子类。 任何新增的参数 (例如门廊类型) 都会让这个层次结构更加复杂。

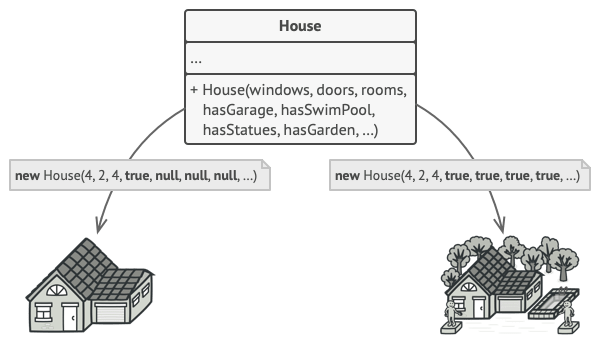

另一种方法则无需生成子类。 你可以在 房屋基类中创建一个包括所有可能参数的超级构造函数, 并用它来控制房屋对象。 这种方法确实可以避免生成子类, 但它却会造成另外一个问题。

拥有大量输入参数的构造函数也有缺陷: 这些参数也不是每次都要全部用上的。

通常情况下, 绝大部分的参数都没有使用, 这使得对于构造函数的调用十分不简洁 (opens new window)。 例如, 只有很少的房子有游泳池, 因此与游泳池相关的参数十之八九是毫无用处的。

# 解决方案

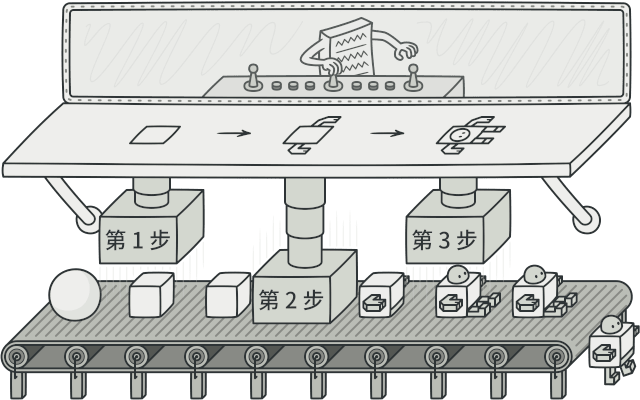

生成器模式建议将对象构造代码从产品类中抽取出来, 并将其放在一个名为_生成器_的独立对象中。

生成器模式让你能够分步骤创建复杂对象。 生成器不允许其他对象访问正在创建中的产品。

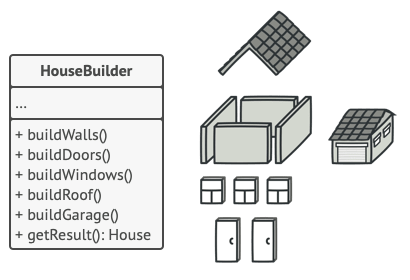

该模式会将对象构造过程划分为一组步骤, 比如 buildWalls创建墙壁和 buildDoor创建房门创建房门等。 每次创建对象时, 你都需要通过生成器对象执行一系列步骤。 重点在于你无需调用所有步骤, 而只需调用创建特定对象配置所需的那些步骤即可。

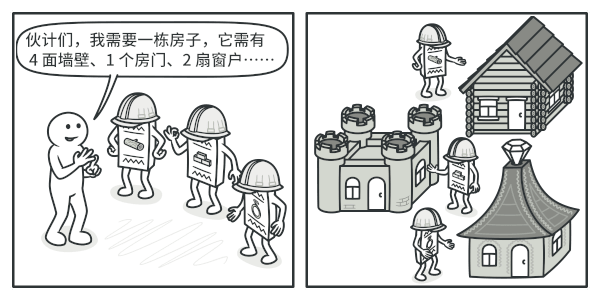

当你需要创建不同形式的产品时, 其中的一些构造步骤可能需要不同的实现。 例如, 木屋的房门可能需要使用木头制造, 而城堡的房门则必须使用石头制造。

在这种情况下, 你可以创建多个不同的生成器, 用不同方式实现一组相同的创建步骤。 然后你就可以在创建过程中使用这些生成器 (例如按顺序调用多个构造步骤) 来生成不同类型的对象。

不同生成器以不同方式执行相同的任务。

例如, 假设第一个建造者使用木头和玻璃制造房屋, 第二个建造者使用石头和钢铁, 而第三个建造者使用黄金和钻石。 在调用同一组步骤后, 第一个建造者会给你一栋普通房屋, 第二个会给你一座小城堡, 而第三个则会给你一座宫殿。 但是, 只有在调用构造步骤的客户端代码可以通过通用接口与建造者进行交互时, 这样的调用才能返回需要的房屋。

# 主管

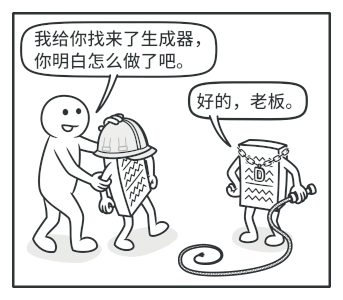

你可以进一步将用于创建产品的一系列生成器步骤调用抽取成为单独的_主管_类。 主管类可定义创建步骤的执行顺序, 而生成器则提供这些步骤的实现。

主管知道需要哪些创建步骤才能获得可正常使用的产品。

严格来说, 你的程序中并不一定需要主管类。 客户端代码可直接以特定顺序调用创建步骤。 不过, 主管类中非常适合放入各种例行构造流程, 以便在程序中反复使用。

此外, 对于客户端代码来说, 主管类完全隐藏了产品构造细节。 客户端只需要将一个生成器与主管类关联, 然后使用主管类来构造产品, 就能从生成器处获得构造结果了。

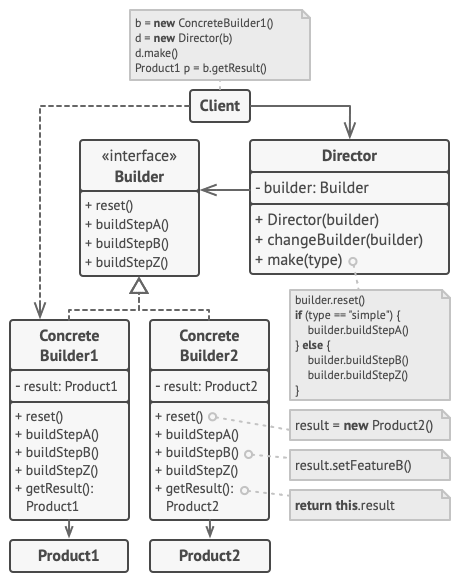

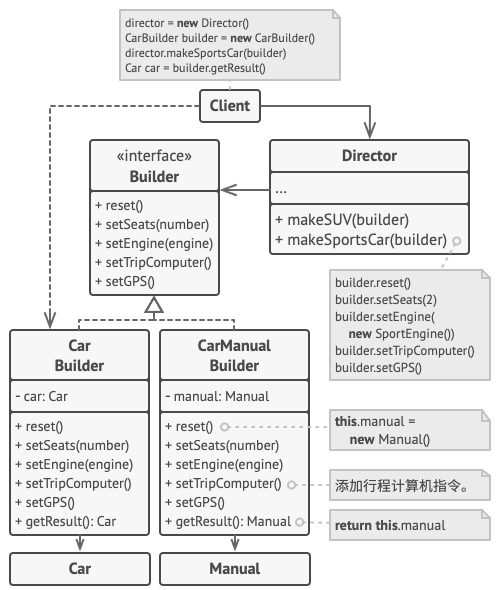

# 生成器模式结构

生成器 (Builder) 接口声明在所有类型生成器中通用的产品构造步骤。

具体生成器 (Concrete Builders) 提供构造过程的不同实现。 具体生成器也可以构造不遵循通用接口的产品。

产品 (Products) 是最终生成的对象。 由不同生成器构造的产品无需属于同一类层次结构或接口。

主管 (Director) 类定义调用构造步骤的顺序, 这样你就可以创建和复用特定的产品配置。

客户端 (Client) 必须将某个生成器对象与主管类关联。 一般情况下, 你只需通过主管类构造函数的参数进行一次性关联即可。 此后主管类就能使用生成器对象完成后续所有的构造任务。 但在客户端将生成器对象传递给主管类制造方法时还有另一种方式。 在这种情况下, 你在使用主管类生产产品时每次都可以使用不同的生成器。

# 伪代码

下面关于生成器模式的例子演示了你可以如何复用相同的对象构造代码来生成不同类型的产品——例如汽车 (Car)——及其相应的使用手册 (Manual)。

分步骤制造汽车并制作对应型号用户使用手册的示例

汽车是一个复杂对象, 有数百种不同的制造方法。 我们没有在 汽车类中塞入一个巨型构造函数, 而是将汽车组装代码抽取到单独的汽车生成器类中。 该类中有一组方法可用来配置汽车的各种部件。

如果客户端代码需要组装一辆与众不同、 精心调教的汽车, 它可以直接调用生成器。 或者, 客户端可以将组装工作委托给主管类, 因为主管类知道如何使用生成器制造最受欢迎的几种型号汽车。

你或许会感到吃惊, 但确实每辆汽车都需要一本使用手册 (说真的, 谁会去读它们呢?)。 使用手册会介绍汽车的每一项功能, 因此不同型号的汽车, 其使用手册内容也不一样。 因此, 你可以复用现有流程来制造实际的汽车及其对应的手册。 当然, 编写手册和制造汽车不是一回事, 所以我们需要另外一个生成器对象来专门编写使用手册。 该类与其制造汽车的兄弟类都实现了相同的制造方法, 但是其功能不是制造汽车部件, 而是描述每个部件。 将这些生成器传递给相同的主管对象, 我们就能够生成一辆汽车或是一本使用手册了。

最后一个部分是获取结果对象。 尽管金属汽车和纸质手册存在关联, 但它们却是完全不同的东西。 我们无法在主管类和具体产品类不发生耦合的情况下, 在主管类中提供获取结果对象的方法。 因此, 我们只能通过负责制造过程的生成器来获取结果对象。

// 只有当产品较为复杂且需要详细配置时,使用生成器模式才有意义。下面的两个

// 产品尽管没有同样的接口,但却相互关联。

class Car is

// 一辆汽车可能配备有 GPS 设备、行车电脑和几个座位。不同型号的汽车(

// 运动型轿车、SUV 和敞篷车)可能会安装或启用不同的功能。

class Manual is

// 用户使用手册应该根据汽车配置进行编制,并介绍汽车的所有功能。

// 生成器接口声明了创建产品对象不同部件的方法。

interface Builder is

method reset()

method setSeats(……)

method setEngine(……)

method setTripComputer(……)

method setGPS(……)

// 具体生成器类将遵循生成器接口并提供生成步骤的具体实现。你的程序中可能会

// 有多个以不同方式实现的生成器变体。

class CarBuilder implements Builder is

private field car:Car

// 一个新的生成器实例必须包含一个在后续组装过程中使用的空产品对象。

constructor CarBuilder() is

this.reset()

// reset(重置)方法可清除正在生成的对象。

method reset() is

this.car = new Car()

// 所有生成步骤都会与同一个产品实例进行交互。

method setSeats(……) is

// 设置汽车座位的数量。

method setEngine(……) is

// 安装指定的引擎。

method setTripComputer(……) is

// 安装行车电脑。

method setGPS(……) is

// 安装全球定位系统。

// 具体生成器需要自行提供获取结果的方法。这是因为不同类型的生成器可能

// 会创建不遵循相同接口的、完全不同的产品。所以也就无法在生成器接口中

// 声明这些方法(至少在静态类型的编程语言中是这样的)。

//

// 通常在生成器实例将结果返回给客户端后,它们应该做好生成另一个产品的

// 准备。因此生成器实例通常会在 `getProduct(获取产品)`方法主体末尾

// 调用重置方法。但是该行为并不是必需的,你也可让生成器等待客户端明确

// 调用重置方法后再去处理之前的结果。

method getProduct():Car is

product = this.car

this.reset()

return product

// 生成器与其他创建型模式的不同之处在于:它让你能创建不遵循相同接口的产品。

class CarManualBuilder implements Builder is

private field manual:Manual

constructor CarManualBuilder() is

this.reset()

method reset() is

this.manual = new Manual()

method setSeats(……) is

// 添加关于汽车座椅功能的文档。

method setEngine(……) is

// 添加关于引擎的介绍。

method setTripComputer(……) is

// 添加关于行车电脑的介绍。

method setGPS(……) is

// 添加关于 GPS 的介绍。

method getProduct():Manual is

// 返回使用手册并重置生成器。

// 主管只负责按照特定顺序执行生成步骤。其在根据特定步骤或配置来生成产品时

// 会很有帮助。由于客户端可以直接控制生成器,所以严格意义上来说,主管类并

// 不是必需的。

class Director is

// 主管可同由客户端代码传递给自身的任何生成器实例进行交互。客户端可通

// 过这种方式改变最新组装完毕的产品的最终类型。主管可使用同样的生成步

// 骤创建多个产品变体。

method constructSportsCar(builder: Builder) is

builder.reset()

builder.setSeats(2)

builder.setEngine(new SportEngine())

builder.setTripComputer(true)

builder.setGPS(true)

method constructSUV(builder: Builder) is

// ……

// 客户端代码会创建生成器对象并将其传递给主管,然后执行构造过程。最终结果

// 将需要从生成器对象中获取。

class Application is

method makeCar() is

director = new Director()

CarBuilder builder = new CarBuilder()

director.constructSportsCar(builder)

Car car = builder.getProduct()

CarManualBuilder builder = new CarManualBuilder()

director.constructSportsCar(builder)

// 最终产品通常需要从生成器对象中获取,因为主管不知晓具体生成器和

// 产品的存在,也不会对其产生依赖。

Manual manual = builder.getProduct()

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

# 生成器模式适合应用场景

使用生成器模式可避免 “重叠构造函数 (telescoping constructor)” 的出现。

假设你的构造函数中有十个可选参数, 那么调用该函数会非常不方便; 因此, 你需要重载这个构造函数, 新建几个只有较少参数的简化版。 但这些构造函数仍需调用主构造函数, 传递一些默认数值来替代省略掉的参数。

class Pizza {

Pizza(int size) { …… }

Pizza(int size, boolean cheese) { …… }

Pizza(int size, boolean cheese, boolean pepperoni) { …… }

2

3

4

5

6

只有在 C# 或 Java 等支持方法重载的编程语言中才能写出如此复杂的构造函数。

生成器模式让你可以分步骤生成对象, 而且允许你仅使用必须的步骤。 应用该模式后, 你再也不需要将几十个参数塞进构造函数里了。

当你希望使用代码创建不同形式的产品 (例如石头或木头房屋) 时, 可使用生成器模式。

如果你需要创建的各种形式的产品, 它们的制造过程相似且仅有细节上的差异, 此时可使用生成器模式。

基本生成器接口中定义了所有可能的制造步骤, 具体生成器将实现这些步骤来制造特定形式的产品。 同时, 主管类将负责管理制造步骤的顺序。

使用生成器构造组合 (opens new window)树或其他复杂对象。

生成器模式让你能分步骤构造产品。 你可以延迟执行某些步骤而不会影响最终产品。 你甚至可以递归调用这些步骤, 这在创建对象树时非常方便。

生成器在执行制造步骤时, 不能对外发布未完成的产品。 这可以避免客户端代码获取到不完整结果对象的情况。

# 实现方法

清晰地定义通用步骤, 确保它们可以制造所有形式的产品。 否则你将无法进一步实施该模式。

在基本生成器接口中声明这些步骤。

为每个形式的产品创建具体生成器类, 并实现其构造步骤。

不要忘记实现获取构造结果对象的方法。 你不能在生成器接口中声明该方法, 因为不同生成器构造的产品可能没有公共接口, 因此你就不知道该方法返回的对象类型。 但是, 如果所有产品都位于单一类层次中, 你就可以安全地在基本接口中添加获取生成对象的方法。

考虑创建主管类。 它可以使用同一生成器对象来封装多种构造产品的方式。

客户端代码会同时创建生成器和主管对象。 构造开始前, 客户端必须将生成器对象传递给主管对象。 通常情况下, 客户端只需调用主管类构造函数一次即可。 主管类使用生成器对象完成后续所有制造任务。 还有另一种方式, 那就是客户端可以将生成器对象直接传递给主管类的制造方法。

只有在所有产品都遵循相同接口的情况下, 构造结果可以直接通过主管类获取。 否则, 客户端应当通过生成器获取构造结果。

# 生成器模式优缺点

# 优点

- 你可以分步创建对象, 暂缓创建步骤或递归运行创建步骤。

- 生成不同形式的产品时, 你可以复用相同的制造代码。

- 单一职责原则。 你可以将复杂构造代码从产品的业务逻辑中分离出来。

# 缺点

- 由于该模式需要新增多个类, 因此代码整体复杂程度会有所增加。

# 与其他模式的关系

在许多设计工作的初期都会使用工厂方法模式 (opens new window) (较为简单, 而且可以更方便地通过子类进行定制), 随后演化为使用抽象工厂模式 (opens new window)、 原型模式 (opens new window)或生成器模式 (opens new window) (更灵活但更加复杂)。

生成器 (opens new window)重点关注如何分步生成复杂对象。 抽象工厂 (opens new window)专门用于生产一系列相关对象。 _抽象工厂_会马上返回产品, _生成器_则允许你在获取产品前执行一些额外构造步骤。

你可以在创建复杂组合模式 (opens new window)树时使用生成器 (opens new window), 因为这可使其构造步骤以递归的方式运行。

你可以结合使用生成器 (opens new window)和桥接模式 (opens new window): _主管_类负责抽象工作, 各种不同的_生成器_负责_实现_工作。

抽象工厂 (opens new window)、 生成器 (opens new window)和原型 (opens new window)都可以用单例模式 (opens new window)来实现。

# 基本思想和原则

将一个复杂对象的构建和它的表示分离,使同样的构建过程可以创建不同的表示。

使用 Builder 类封装类实例的创建过程,客户代码使用各个 Builder 来构建对象而不是直接使用 new 创建类实例。

# 动机

当一个类中某个方法中的内部调用顺序不同,会产生不同的结果时,可以考虑使用建造者模式。将产生特定调用顺序的类实例用 Builder 进行封装,供客户代码使用可以简化整个对象创建过程。当需要产生新的调用顺序地类实例时,只需要创建对应的 Builder 即可。

# 示例代码

from __future__ import annotations

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

from typing import Any

class Builder(ABC):

"""

The Builder interface specifies methods for creating the different parts of

the Product objects.

"""

@property

@abstractmethod

def product(self) -> None:

pass

@abstractmethod

def produce_part_a(self) -> None:

pass

@abstractmethod

def produce_part_b(self) -> None:

pass

@abstractmethod

def produce_part_c(self) -> None:

pass

class ConcreteBuilder1(Builder):

"""

The Concrete Builder classes follow the Builder interface and provide

specific implementations of the building steps. Your program may have

several variations of Builders, implemented differently.

"""

def __init__(self) -> None:

"""

A fresh builder instance should contain a blank product object, which is

used in further assembly.

"""

self.reset()

def reset(self) -> None:

self._product = Product1()

@property

def product(self) -> Product1:

"""

Concrete Builders are supposed to provide their own methods for

retrieving results. That's because various types of builders may create

entirely different products that don't follow the same interface.

Therefore, such methods cannot be declared in the base Builder interface

(at least in a statically typed programming language).

Usually, after returning the end result to the client, a builder

instance is expected to be ready to start producing another product.

That's why it's a usual practice to call the reset method at the end of

the `getProduct` method body. However, this behavior is not mandatory,

and you can make your builders wait for an explicit reset call from the

client code before disposing of the previous result.

"""

product = self._product

self.reset()

return product

def produce_part_a(self) -> None:

self._product.add("PartA1")

def produce_part_b(self) -> None:

self._product.add("PartB1")

def produce_part_c(self) -> None:

self._product.add("PartC1")

class Product1():

"""

It makes sense to use the Builder pattern only when your products are quite

complex and require extensive configuration.

Unlike in other creational patterns, different concrete builders can produce

unrelated products. In other words, results of various builders may not

always follow the same interface.

"""

def __init__(self) -> None:

self.parts = []

def add(self, part: Any) -> None:

self.parts.append(part)

def list_parts(self) -> None:

print(f"Product parts: {', '.join(self.parts)}", end="")

class Director:

"""

The Director is only responsible for executing the building steps in a

particular sequence. It is helpful when producing products according to a

specific order or configuration. Strictly speaking, the Director class is

optional, since the client can control builders directly.

"""

def __init__(self) -> None:

self._builder = None

@property

def builder(self) -> Builder:

return self._builder

@builder.setter

def builder(self, builder: Builder) -> None:

"""

The Director works with any builder instance that the client code passes

to it. This way, the client code may alter the final type of the newly

assembled product.

"""

self._builder = builder

"""

The Director can construct several product variations using the same

building steps.

"""

def build_minimal_viable_product(self) -> None:

self.builder.produce_part_a()

def build_full_featured_product(self) -> None:

self.builder.produce_part_a()

self.builder.produce_part_b()

self.builder.produce_part_c()

if __name__ == "__main__":

"""

The client code creates a builder object, passes it to the director and then

initiates the construction process. The end result is retrieved from the

builder object.

"""

director = Director()

builder = ConcreteBuilder1()

director.builder = builder

print("Standard basic product: ")

director.build_minimal_viable_product()

builder.product.list_parts()

print("\n")

print("Standard full featured product: ")

director.build_full_featured_product()

builder.product.list_parts()

print("\n")

# Remember, the Builder pattern can be used without a Director class.

print("Custom product: ")

builder.produce_part_a()

builder.produce_part_b()

builder.product.list_parts()

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

输出

Standard basic product:

Product parts: PartA1

Standard full featured product:

Product parts: PartA1, PartB1, PartC1

Custom product:

Product parts: PartA1, PartB1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

"""

*What is this pattern about?

It decouples the creation of a complex object and its representation,

so that the same process can be reused to build objects from the same

family.

This is useful when you must separate the specification of an object

from its actual representation (generally for abstraction).

*What does this example do?

The first example achieves this by using an abstract base

class for a building, where the initializer (__init__ method) specifies the

steps needed, and the concrete subclasses implement these steps.

In other programming languages, a more complex arrangement is sometimes

necessary. In particular, you cannot have polymorphic behaviour in a constructor in C++ -

see https://stackoverflow.com/questions/1453131/how-can-i-get-polymorphic-behavior-in-a-c-constructor

- which means this Python technique will not work. The polymorphism

required has to be provided by an external, already constructed

instance of a different class.

In general, in Python this won't be necessary, but a second example showing

this kind of arrangement is also included.

*Where is the pattern used practically?

*References:

https://sourcemaking.com/design_patterns/builder

*TL;DR

Decouples the creation of a complex object and its representation.

"""

# Abstract Building

class Building:

def __init__(self) -> None:

self.build_floor()

self.build_size()

def build_floor(self):

raise NotImplementedError

def build_size(self):

raise NotImplementedError

def __repr__(self) -> str:

return "Floor: {0.floor} | Size: {0.size}".format(self)

# Concrete Buildings

class House(Building):

def build_floor(self) -> None:

self.floor = "One"

def build_size(self) -> None:

self.size = "Big"

class Flat(Building):

def build_floor(self) -> None:

self.floor = "More than One"

def build_size(self) -> None:

self.size = "Small"

# In some very complex cases, it might be desirable to pull out the building

# logic into another function (or a method on another class), rather than being

# in the base class '__init__'. (This leaves you in the strange situation where

# a concrete class does not have a useful constructor)

class ComplexBuilding:

def __repr__(self) -> str:

return "Floor: {0.floor} | Size: {0.size}".format(self)

class ComplexHouse(ComplexBuilding):

def build_floor(self) -> None:

self.floor = "One"

def build_size(self) -> None:

self.size = "Big and fancy"

def construct_building(cls) -> Building:

building = cls()

building.build_floor()

building.build_size()

return building

def main():

"""

>>> house = House()

>>> house

Floor: One | Size: Big

>>> flat = Flat()

>>> flat

Floor: More than One | Size: Small

# Using an external constructor function:

>>> complex_house = construct_building(ComplexHouse)

>>> complex_house

Floor: One | Size: Big and fancy

"""

if __name__ == "__main__":

import doctest

doctest.testmod()

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

ref:patterns/creational/builder.py · imoyao/python-patterns - Gitee.com (opens new window)

# 优点

建造者模式对一个类产生具体实例做了相应的封装,使客户代码不需要了解具体类的内部细节,可以直接使用相应的 Builder 来创建实例。各个 Builder 之间具有很好的隔离性,都可以独立做改变而不会互相影响。